Image source: http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8299/7866771910_c694e6cabb.jpg

Sometimes a book gets under your skin. The words make you angry so that you want to hurl the hardcover across the wall. Or quickly delete your library loan from the Kindle and pray that you never read another word of it again. Even worse, when you vent your anger, you find yourself losing friends because of your opinion, and at the best they gently chide you for misreading the book and trying to look at the big picture.

Sometimes a book gets under your skin. The words make you angry so that you want to hurl the hardcover across the wall. Or quickly delete your library loan from the Kindle and pray that you never read another word of it again. Even worse, when you vent your anger, you find yourself losing friends because of your opinion, and at the best they gently chide you for misreading the book and trying to look at the big picture.

That happened to me three times this summer, with three different books. I am only going to talk about the last book, because it was the only one that inspired organized anger. The Gospel According to Christ triggered a more visceral reaction, one that does not translate into coherent words, and I simply do not get the appeal behind Game of Thrones and the complex world it presents, at least not enough for a blog post. Also, I don't want to get sucked into having to look at it as part of an encompassing story, because then I will get no writing done.

Margaret

Peterson Haddix's Shadow Children series focuses on a future

where parents can only have two kids. Doesn't sound so bad, does it? Not for

the so-called titular characters, third-born boys and girls who have to hide from the

Government. The Government deems that third-born children

deprive the world of much-needed food, despite banning certain farming

practices for no reason and will kill any "ex-nays" that they

find.

I do not

deny that the books are well-written. Each book has a fast-paced story. No, my

concern is deception, and how the supposed heroes use deception in one book, Among

the Betrayed.

SPOILER

WARNING: If you have not read the books, do not read more. This mainly concerns Among

the Betrayed, The Hunger Games, V for Vendetta and Ender's

Game.

Image source: http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7168/6485398549_fdafa2c315.jpg

Image source: http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7168/6485398549_fdafa2c315.jpg

Dystopia

novels need deception. Governments need to trick individuals into believing a

particular mindset, like that choices are a bad idea or that books deserve

bonfires, after all. Fighting for the truth becomes a difficult battle,

especially if said governments use torture and brainwashing to smoke out

potential rebellion.

When

heroes' allies use deception, to trick them however, the heroes usually get

angry. No one likes a liar, let alone a liar who's supposed to be your friend.

More importantly, no hero wants to become a pawn. By definition, heroes have to

take charge of the plot and undergo a great change. In addition, they usually

get tricked into doing horrible things, like murdering a horde of aliens, or

made to suffer horrible things to undergo character development. This spoiler

quote from Ender's Game sums it up best:

"I didn't want to kill them at all. I didn't want to kill

anybody! I'm not a killer . . . you made me do it, you tricked me into

it!" He was crying. He was out of control.

"Of course we tricked you into it. That's the whole

point," Graff said. "It had to be a trick, or you couldn't have done

it."

(Card 298)

Among the Betrayed has the most extreme

form of child-friendly deception, to see if a thirteen-year old girl was

willing to sell out illegal children to the government. Nina Idi committed no

crime, but a would-be boyfriend betrayed her. She's given a plea deal in prison

to gain other illegal children's trust to save her own life. Once she refuses

to act on that deal, after 150 pages of not going one way or the other, the

"hating" man who offers the plea deal reveals that she can live, that

he's on her side.

Nina does

not get angry when she learns about the test. She does not even suffer

emotional trauma or trust issue afterwards. She thanks everyone involved, adult

and child, for giving her a "second chance" after thinking her a

traitor. She's able to forgive the "hating man" for putting her

through months of fear just to see if she would sell out shadow children, and

this is his defense when she asks why she should trust him:

"Nina, we live in complicated times . . . Don't you see how

muddy everyone's intentions get, how people end up doing the wrong things for

the right reasons, and the right things for the wrong reasons-and all any of us

can do is try our hardest and have faith that somehow, someday, it will all

work out?"

(Peterson Haddix 152)

Aside from the abstract terms used to describe the hating man's actions, he does not believe that what he did was wrong. He does say Nina did not deserve to get arrested, but he had made the call at the book's beginning. He uses the term "we" instead of "I" and feels entitled to engaging in deception to save hundreds of children's lives. He takes no responsibility for her suffering, only for her salvation.

Aside from the abstract terms used to describe the hating man's actions, he does not believe that what he did was wrong. He does say Nina did not deserve to get arrested, but he had made the call at the book's beginning. He uses the term "we" instead of "I" and feels entitled to engaging in deception to save hundreds of children's lives. He takes no responsibility for her suffering, only for her salvation.

Television

Tropes has a term for this issue: He Who Fights Monsters. As the page describes,

"Something has happened to our Fallen Hero: his village was destroyed, his friends killed, his puppy roasted on an open spit, his bike stolen, whatever. All that matters is that It's Personal, and he feels that the law just isn't suitable enough (or has

become too corrupt and ignorant) to be of any use to him in settling the matter. Oh,

sure, he'll justify his actions by claiming that it's Justice he's

after, not vengeance, but anyone with half a brain can easily see that he's out

for revenge...

unfortunately, we can also see that the more he hunts the cause of his

woes, on the — something that

our "hero" is too blinded by his single-minded goal to realize."

Heroes don't always make easy decisions. Sometimes they have to act like their worst foes, or their allies have to do the dirty work. But a good story explores how they come to those decisions, to emulate the monsters that they battle.

Heroes don't always make easy decisions. Sometimes they have to act like their worst foes, or their allies have to do the dirty work. But a good story explores how they come to those decisions, to emulate the monsters that they battle.

Most

dystopian works acknowledge moral ambiguity when heroes engage in deception. The

Hunger Games calls out any rebel or rebel leader who will sacrifice

children for a cause. V for Vendetta shows that the path to

stripping someone of fear will have said person hating you for at least a few

minutes, and revealing bitterness about the ordeal, even if they learn. Ender's

Game has Colonel Graff admitting that what he did to Ender,

making him a war general at the age of twelve, borders on the unethical, even

though his actions may have saved the human race and he doesn't even give Ender

a therapist to cope with the trauma of having murdered millions. The reader can

decide in these works if the heroes' allies did the right thing, if the hero

can atone for these actions.

Among the Betrayed offers no such view

into the truth. The test itself has

cool, emotionless logic to it. That cool logic translates into fear, death

threats, and low food supplies. Even if the participants had good intentions

and meant no true harm, their actions made them verge on the line that

separates them from the apparently useless and deadly Government.

The hating man does not

acknowledge that he interrogated a thirteen-year old girl and put her through

rigorous motions to identify her as a criminal. He does not acknowledge that by

imitating the government's popular methods of interrogation, as a double agent,

that he became as bad as its worst Population Police. He merely uses the excuse

above that one cannot really identify people's intentions in such a paranoid

era, and Nina never brings up the issue again. What's more, all of the

participants seem to agree with the hating man's methods, with only one

asserting that Nina was trustworthy.

The second issue that I

have, in addition to the He Who Fights Monsters issue, is Nina's forgiveness

and ability to move on. In the beginning she feels angry, betrayed and

desperate to try anything to live. She's a thirteen-year old ingénue who loved

the wrong boy. Throughout the story she bonds with the children she was

supposed to betray, and could have ended her suffering at any point by

revealing the plea deal offered. She does not express frustration over that

latter point, instead accepting that she has grown into a person who can let go

of hatred while doing the right thing.

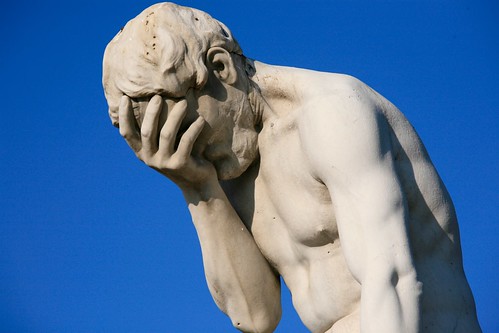

The lack of anger seems

implausible. In fiction anger has its place as a form of release. In real life

the emotion is destructive, poisoning. Writing about a child punching another

is different from an actual blow being released. While no one physically

injures Nina in the story or tortures her, they all treat her as an enemy in

one chapter and then pick corn with her in the next. Her ability to still trust

comes up, but some closure could have been welcome, an acknowledgement that

putting a girl through emotional stress.

Once again, Among

the Betrayed is not a terrible book. It's in fact well-written,

fast-paced and a thrill to read at night. I admire Margaret Peterson Haddix's

ability to tell a terrible story about kids dying for an arbitrary government.

What irks me is the lack of anger, of righteous fury that should spur the

characters forward. Perhaps if the book had received several extra chapters, I

would have been able to chart Nina's growth better and to receive more

closure.

The lesson from this:

allow your characters to get angry, even if it obstructs your story's point.

Especially in a tale with deception, remember this phrase:

"Fool me once,

shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me."

Image source: http://farm3.staticflickr.com/2559/4199675334_66c3e3d61d.jpg

Do not fool the reader.

Show your characters, old and young, as human beings. Allow them to express righteous indignation. Let them call out the heroes for not acting heroic.

No comments:

Post a Comment